Journalcalling #11 – Early Jobs

Journalcalling • January 26, 2021

needed money for my candy addiction and Teen Beat magazines, so before I was old enough to work for anyone else, I sold items door-to-door in my neighborhood. At 10, I lugged around fat catalogues of holiday cards, wrapping paper and address labels and appealed to every neighbor or stranger who opened their door.

Our house was on a corner and a perfect location to operate a Kool Aid stand. I would score the packets from our kitchen cabinet and occasionally raid the freezer for cans of frozen lemonade. After mixing and carrying sloshing pitchers of sticky drink out to my storefront — a tray table perched outside our fence gate — I’d beg the adults who walked to and from the bus stop to purchase a cup. A few kind souls obliged.

I soon expanded to a more captive audience. With a couple of friends, I ran carnivals in our driveway. At the entrance to The Peanut Carnival, I sold bags of peanuts to neighborhood kids who could exchange them to play homemade games of ring toss and corn hole. It was a savvy way to consolidate the cash and more lucrative than selling Kool Aid.

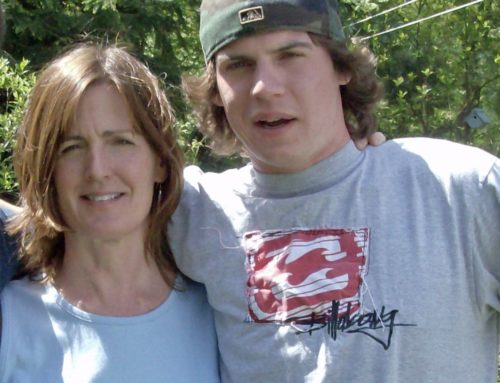

When I was 15, I left my entrepreneur days behind to work at Clinton Nurseries. Each summer morning, my mom would drop me off in the parking lot overlooking acres of greenhouses. My first assignment was to join the field hands tagging rhododendron bushes. The sun beat down on my hunched back, and I was thankful for the days I was sent to a hoop house where the tarps had been removed and breezes could drift in.

As the mornings wore on, I’d search the horizon for the large blue food truck to roll in bringing a cloud of dust that signaled a short break. I rarely had enough money to order a fried egg sandwich or other greasy delicacy, and would instead reach into the brown bag my mom had packed for an apple or early bite into my liverwurst sandwich.

Eventually, I was promoted to the propagation department. I sat at a table in a small room with four or five other girls who made small cuttings from the branches of shrubs. We talked as we worked, until the boss popped in, and I still have a faint scar where my sharp-edged tool snipped my thumb. At the end of each week, I was thrilled to be handed a small manila envelope with my name and pay rate handwritten on it with cash and coins inside.

After that summer, I gave up working with shrubbery and cleaned myself up. My typing teacher Mrs. Reinsch had kept me after class one day to tell me about a job as a bank teller. For the interview with Eveylyn Joyner, the no-nonsense but gracious manager of Deep River Savings Bank, I wore one of my best outfits — light green wool pants and a matching plaid vest.

I loved the papery-ness of the job — counting out the bills and keeping my station stocked with stacks of withdrawal and deposit slips. For every transaction, I had to carefully feed a slip into a large teletype machine to create a receipt.

Before the end of each day, I was required to balance my drawer to the penny which sometimes meant a search with the boss for an erroneously entered transaction or math mistake. Overall, I was pretty good at this rudimentary bookkeeping and enjoyed greeting customers at my window. I kept my teller job through high school — working summers, weekends and during school vacations.

The ladies at the bank embraced me — the only teenager among them — and taught me what it looked like to be a professional in a serious industry. When I beelined to the drive-through window because my boyfriend had pulled up, they gently steered me back to my counter.

They exchanged glances and squinted at me when my friends dropped me off for work the Saturday after prom. We had enjoyed a post-prom overnight in the woods, and I had arrived with my gown over my arm. When my mom refused to pick me up at the end of the day, not one of them offered to drive me home. I set off on a very long walk of shame.

From there, I somehow veered off to manufacturing. Beckson Pump Services had a small factory in my hometown where I was introduced to the toxic chemical THF. Poured into a small tray in front of me, I’d dip in the bottom of plastic bilge pumps to melt the ends then “weld” on the feet. I used my fingers to wipe off the excess gooey plastic. Ventilation was an open window. Ahh, the 70s. I replenished my lungs with fresh air by riding my bike the five miles to and from this crazy job.

I returned to outdoor employment, this time at the ocean, where my swim team experience and CPR training got me a job as a lifeguard and swim instructor at my town beach. Unfortunately, it only lasted one summer. When I decided to drop out of Bryant College after two years — where I was sinking as an accounting major — my mom said I had to get serious and get a real job. That meant I had to give up a coveted position I had landed as a lifeguard at a Connecticut State Park to take a job at … a large accounting firm.

It quickly became obvious I did not know my way around a spreadsheet, but the managing partner was a friend of my uncle’s and they kept me on as their proofreader. I became a whiz at an adding-machine tapping my fingers across the keys through columns of numbers at lightning speed. I had my own office with a glass wall overlooking the city, and this made me feel accomplished. After two years, the ceiling seemed a bit low, and I was inspired to go back to college and leave accounting behind for good.